Koperets, een piëta van Andrea Mannuchi voor de heer Lord Nassau Cowper 3/

PS/ Click on any photograph and scroll along in the original size!

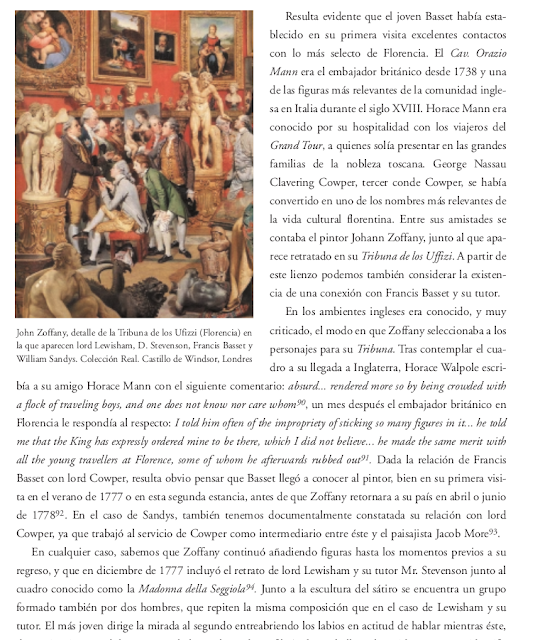

Wat bijzonder is aan deze gravure is dat er het koninklijke Brittania wapen onder staat uit die tijd. Ook is die meneer Nassau Cowper 3 een grootmeester van de Le Grand Tour geweest. Die was belangrijk voor de groei van de geillustreerde pers en de verspreiding van kennis over de wereld.

De graveur Anrea Mannuchi del Sarto komt uit een gerenommeerde Italiaanse kunstenaars familie waarvan er al vele katholieke kunst bekend was in de 15 e eeuw! Ook is er een verband tussen Nederland en Engeland op Koninklijk vlak. Nassau zegt het al, een spruit uit het Willemsgeslacht en dergelijke. De orangistenbeweging bestaat nu nog in delen van Ierland en Schotland.

Het is een opdracht van Nassau Cowper aan Andrea Mannucchi. Hij sponsorde ook een restauratie van een marmeren voorstelling van een Pieta, ik geloof in Milaan, waarschijnlijk als mecenas der kunsten in zijn Grand Tour spoor. De lijst is denk ik ca. 1800 dus ook rond de productie tijd 1780.

Eiken paneel ter afwerking, gerold glas met inundaties, handwerk, en een gefineerde lijst van eiken.

Het is een zeldzaam object gezien ik ook maar niet dan ook werkelijk niets kon vinden van de combi Nassau/Manuchi. De grootte zegt ook iets, folio formaat. Dat gaat niet zomaar in een alledaagse binding van een boekje destijds. Ik vermoed dat het dus uit die Orangisten hoek afkomstig is. M

The Grand Tour was the 17th- and 18th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a chaperone, such as a family member) when they had come of age (about 21 years old).

The custom — which flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transport in the 1840s and was associated with a standard itinerary — served as an educational rite of passage. Though the Grand Tour was primarily associated with the British nobility and wealthy landed gentry, similar trips were made by wealthy young men of other Protestant Northern European nations, and, from the second half of the 18th century, by some South and North Americans.

By the mid-18th century, the Grand Tour had become a regular feature of aristocratic education in Central Europe as well, although it was restricted to the higher nobility. The tradition declined as enthusiasm for neo-classical culture waned, and with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel—an era in which Thomas Cook made the "Cook's Tour" of early mass tourism a byword.

The New York Times in 2008 described the Grand Tour in this way:

Three hundred years ago, wealthy young Englishmen began taking a post-Oxbridge trek through France and Italy in search of art, culture and the roots of Western civilization. With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months (or years) to roam, they commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.[1]

The primary value of the Grand Tour lay in its exposure to the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music.

A Grand Tour could last anywhere from several months to several years. It was commonly undertaken in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor. The legacy of the Grand Tour lives on to the modern day and is still evident in works of travel and literature. From its aristocratic origins and the permutations of sentimental and romantic travel to the age of tourism and globalization, the Grand Tour still influences the destinations tourists choose and shapes the ideas of culture and sophistication that surround the act of travel.[2]

In essence, the Grand Tour was neither a scholarly pilgrimage nor a religious one,[3] though a pleasurable stay in Venice and a residence in Rome were essential. Catholic Grand Tourists followed the same routes as Protestant Whigs. Since the 17th century, a tour to such places was also considered essential for budding artists to understand proper painting and sculpture techniques, though the trappings of the Grand Tour—valets and coachmen, perhaps a cook, certainly a "bear-leader" or scholarly guide—were beyond their reach.

The advent of popular guides, such as the book An Account of Some of the Statues, Bas-Reliefs, Drawings, and Pictures in Italy published in 1722 by Jonathan Richardson and his son Jonathan Richardson the Younger, did much to popularise such trips, and following the artists themselves, the elite considered travel to such centres as necessary rites of passage. For gentlemen, some works of art were essential to demonstrate the breadth and polish they had received from their tour.

In Rome, antiquaries like Thomas Jenkins were also dealers and were able to sell and advise on the purchase of marbles; their price would rise if it were known that the Tourists were interested. Coins and medals, which formed more portable souvenirs and a respected gentleman's guide to ancient history were also popular. Pompeo Batoni made a career of painting the English milordi posed with graceful ease among Roman antiquities. Many continued on to Naples, where they also viewed Herculaneum and Pompeii, but few ventured far into Southern Italy, and fewer still to Greece, then still under Turkish rule.

Earl Cowper (pronounced "Cooper") was a title in the Peerage of Great

Britain. It was created in 1718 by George I for William Cowper, 1st

Baron Cowper, his first Lord Chancellor, with remainder in default of

male issue of his own to his younger brother, Spencer Cowper. Cowper

had already been created Baron Cowper of Wingham in the County of

Kent, in the Peerage of England on 14 December 1706, with normal

remainder to the heirs male of his body, and was made Viscount

Fordwich, in the County of Kent, at the same time as he was given the

earldom, also Peerage of Great Britain and with similar remainder. He

was the great-grandson of William Cowper, who was created a Baronet,

of Ratling Court in the County of Kent, in the Baronetage of England on

4 March 1642. The latter was succeeded by his grandson, the second

Baronet. He represented Hertford in Parliament. He was succeeded by

his eldest son, the aforementioned William Cowper, the third Baronet,

who was elevated to the peerage as Baron Cowper in 1706 and made

Earl Cowper in 1718. In 1706 Lord Cowper married as his second wife

Mary Clavering, daughter of John Clavering, of Chopwell, County

Durham.

William Cowper, 1st Earl Cowper.

Lord Cowper was succeeded by his son, the second Earl.

He assumed the additional surname of Clavering. Cowper married Lady Henrietta, younger daughter of Henry de Nassau d'Auverquerque, 1st Earl of Grantham, a relative of the Dutch House of Orange-Nassau, and a count of the Holy Roman Empire. On the death of Lady Cowper's elder sister, Lady Frances Elliot, in 1772, the second Earl's son, the third Earl became Lord Grantham's heir general, and on 31 January 1778 he was created a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire (Reichsfürst) by the Emperor Joseph II. [1] He was allowed by George III to bear this title in Great Britain.

In the history of the Dutch Republic, Orangism or prinsgezindheid

("pro-prince stance") was a political force opposing the Staatsgezinde

(pro-Republic) party. Orangists supported the princes of Orange as

Stadtholders (a position held by members of the House of Orange)

and military commanders of the Republic, as a check on the power of

the regenten. [1]:12 The Orangist party drew its adherents largely from

traditionalists – mostly farmers, soldiers, noblemen and orthodox

Catholic and Protestant preachers, though its support fluctuated

heavily over the course of the Republic's history and there were never

clear-cut socioeconomic divisions. [1]:13, wiki

.jpg)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment